It is currently 1:17PM on the first Monday in May, and I am not taking my hands off of this keyboard until I have finished writing this newsletter, and it has been sent out.

I decided that I would explain this year’s Met Gala theme to you, yesterday. As you’re probably aware, the Met Gala is today! I love chaos!

My notes have all been written down in chronological order, and now the last step is to translate them to you in the quickest, most digestible way possible. Remember, I am a fashion history nerd that reads textbooks for fun, so making this quick is really subjective; humor me, it’s not like I’m making you pay for this.

Without further ado, let’s get into the ‘Gilded Glamour’ of it all.

Tonights gala is part two of the off schedule, In America: A Lexicon of Fashion, that we experienced on September 13 of last year. While this years extension of the exhibit is titled, In America: An Anthology of Fashion, it is important to note, that the theme of the gala is ‘Gilded Glamour’.

The updated exhibit will give more background and historical context to Lexicon; there will be a greater focus on the evolution and the unsung heroes of American fashion.

Gilded glamour on the other hand, refers to The Gilded Age (1870-1900); a term coined by Mark Twain in 1873, by a book of the same title. The term gilded is defined as both, “covered thinly with gold leaf or gold paint,” and “wealthy and privileged.” Let’s start a drinking game; take a shot every time you see a celebrity wearing a gold dress and calling it a day for “being in theme.”

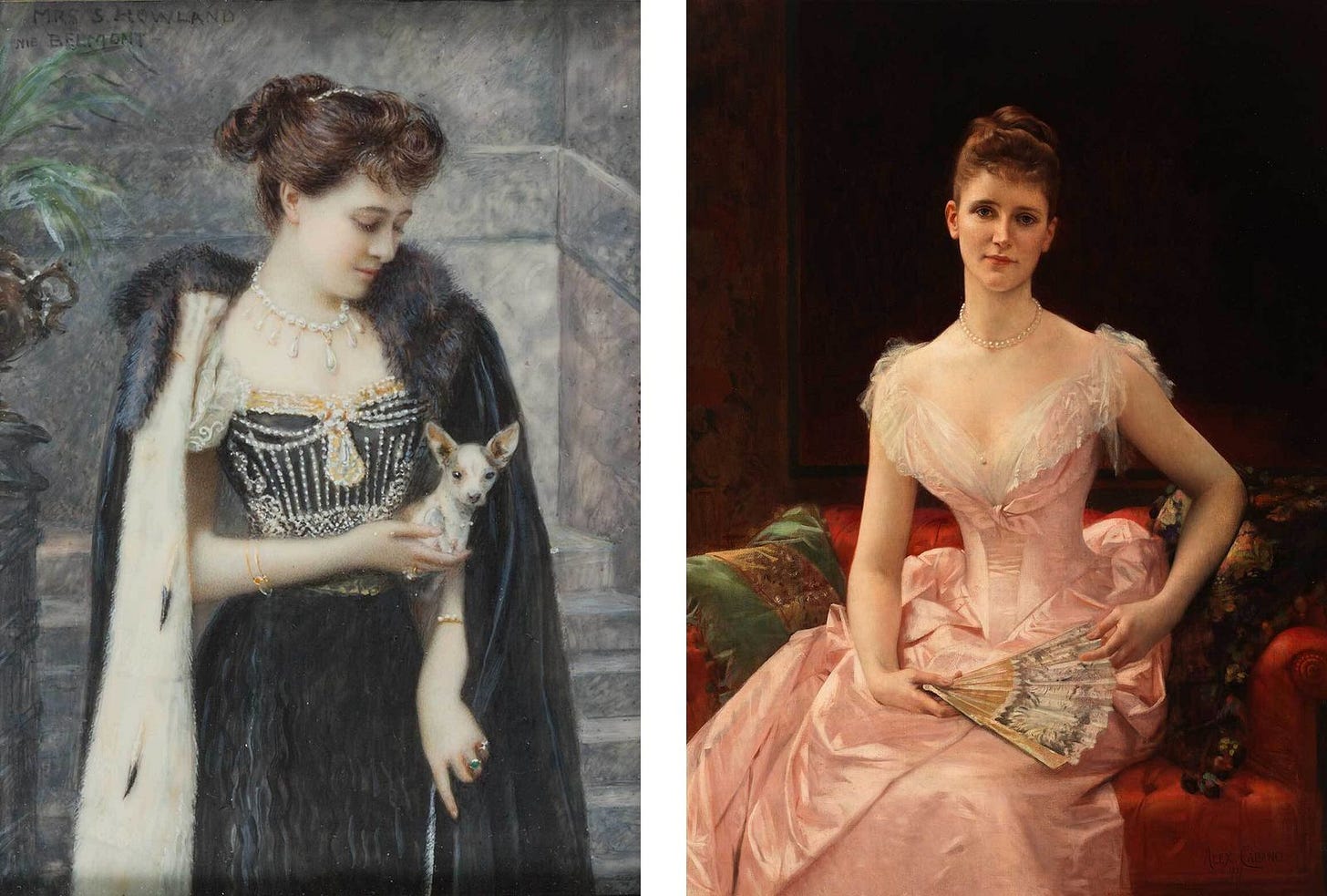

Anyway, the Gilded Age brought the rise of “new money” with names like Vanderbilt and Rockefeller. The oil industry and railroad industries were quickly expanding, and so was the industrialization wealth gap. Mrs. Astor and her 400 were quickly kicked to the curb by the likes of the Vanderbilts, and the women of the Gilded Age quickly stole my maximalist heart.

The bustle, introduced in the 1860s, became one of the most prominent features of gilded age dress. If you’re a regular reader of the newsletter or follow me on TikTok, you’ve probably seen me refer to bustles and panniers as the OG BBL effect. Rather than being circular, like that of crinoline, bustles made the body look more full in the back than in the front. In the late 1860s, there was a small focus on the back of the skirt by changing the shape of the crinoline. A variety that typically focused on hoops only at the back and sides was worn, known as crinolettes or half hoops.

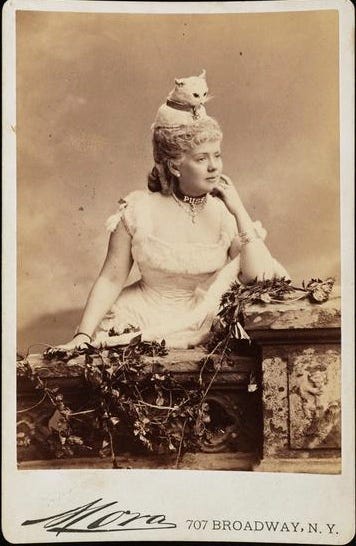

In the early 1870s the bustle was regularly used to elongate a women’s backside. However, from 1876-1882, ‘the natural form’ gained popularity, decreasing exaggeration on the bustle, and creating a more “natural” body; dresses were almost skintight. Princess line dresses were introduced by House of Worth; Worth refined crinoline, making it more narrow, before forgetting about it all together, and created a straight shaped gown without a defined waist known as the princess line. During this times, corsets and bodices had vertical seems as opposed to horizontal ones. Long sleeves, lace collars, and high neck lines were also popular with this style of dress. Hats were a popular accessory, and tended to be highly embellished; sometimes with lace and flowers, other times with whole ass birds.

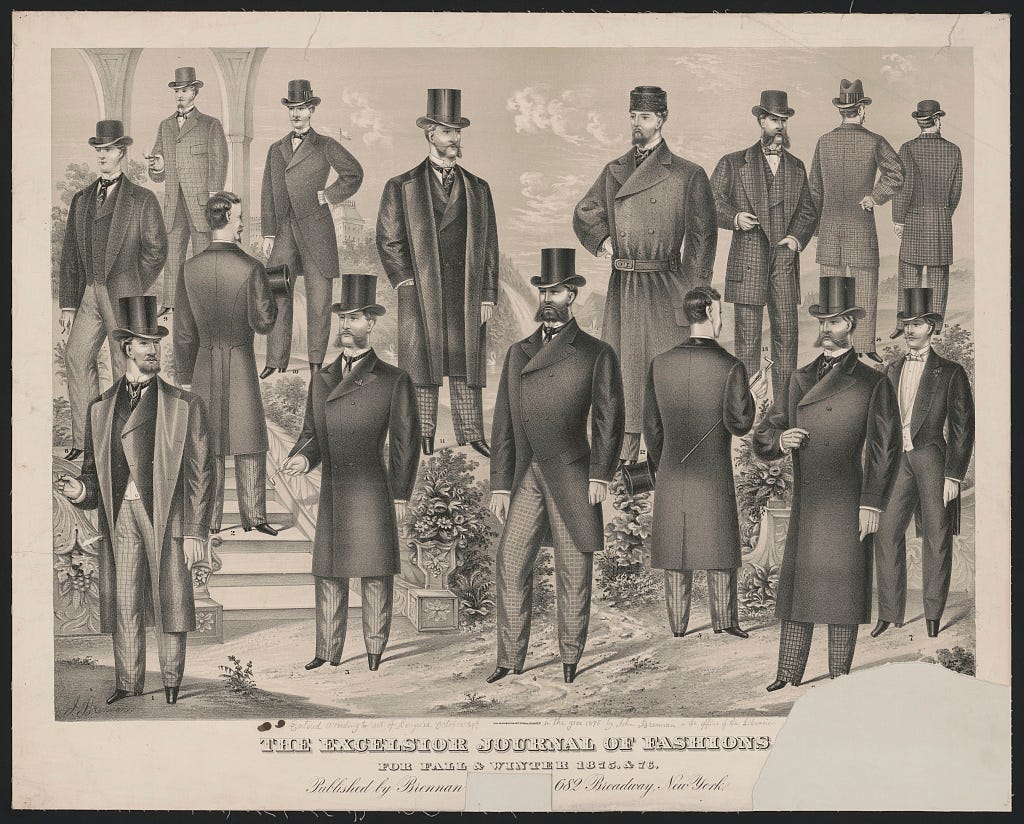

My knowledge of menswear is not as strong, but during this time men sported multi-piece suits, and top hats were also often worn.

Because of all the new synthetic dyes, clothing during this time was very vibrant and rich in color; it was popular to layer different colors, and plaid also had a moment.

By the time 1883 came around, bustles were back better than ever. Given that innovation was booming, fabrics were not only cheaper, but quicker to produce. Therefore, women’s dress often found itself adorned in different fabrics, textures, and embellishments; black Chantilly lace was all the rage. The aesthetic of the late 1870s and early 1880s became a lot busier. Bustles became more elaborate and undergarments became more complex in order to support them. Things like cushions filled with hair and steel springs were used in order to achieve the desired look, as the bustle became more of a sharper “shelf.” More is more after all.

These women were rich, they were fashionable, they did not dream of labor. Even if they did, their clothing wouldn’t allow for it. Clothes and accessories were seen as status symbols, and the more impractical the outfit, the more money you had. Women needed help putting on their complex undergarments, bustles, and corsets, just so that they could, well, exist.

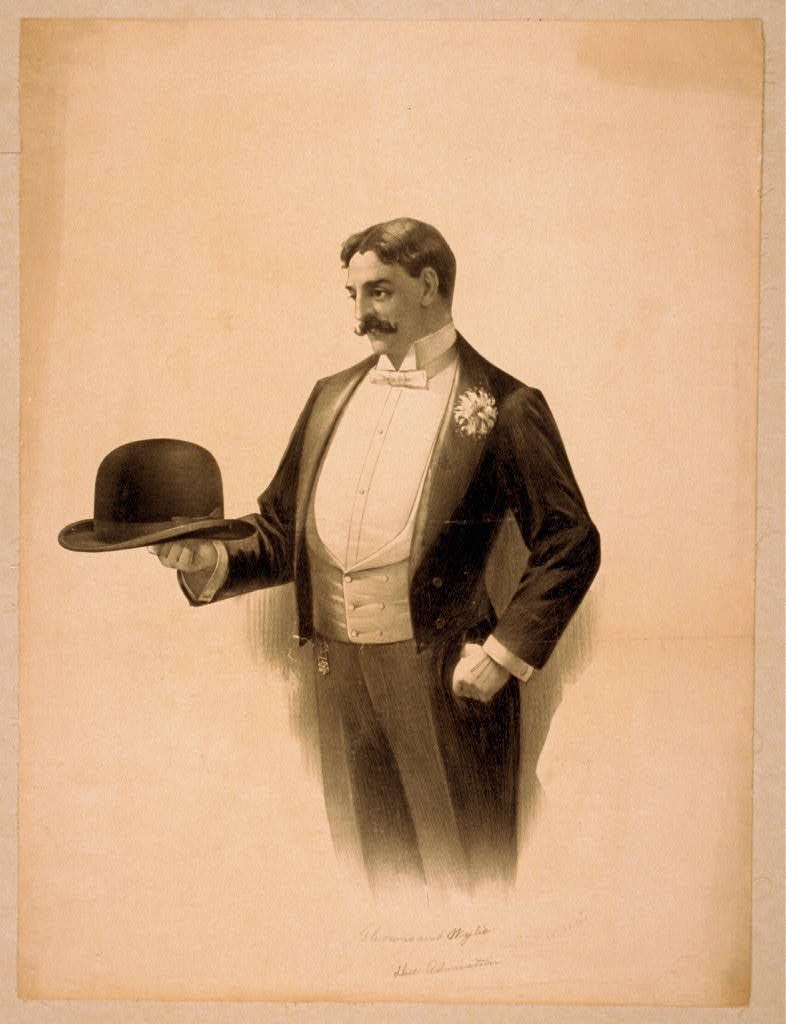

Menswear in the 1880s became less baggy, and the tuxedo is said to have been introduced; take a shot every time you see a celebrity wearing a plain black tux at the Met Gala. Clothing that was worn solely as sportswear also became popular for men.

The most exciting and intriguing part of the 1880s, though, had to have been the extravagant costume parties. Kate Feering Strong’s dead cat headpiece, and gown with sewn in cat parts lives in my head rent free. Also the ‘PUSS’ necklace, come ON! You can’t tell me anyone at the Vanderbilt ball was doing it like her.

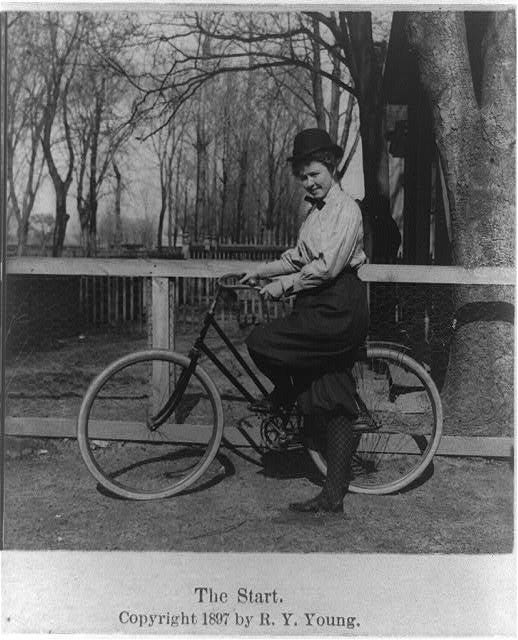

By the time the 1890s came around, bell-shaped skirts and leg of mutton sleeves were rising in popularity. Those waists were SNATCHED. This time also brought the introduction of shirtwaist ensembles (tailored like men’s dress shirts, but feminized with colors and trimmings) and “bicycling costumes” for women; bloomers were some of the more “extreme” new sportswear options for women. As women were spending more time outside of the house, movability became a priority. Sleeve lengths and necklines started to see more variety, depending on what time of day it was.

Menswear during this decade consisted of a lot of stiff, high collars, and jackets were often worn unbuttoned. It was also common to see men wearing brightly colored shirts and waistcoats, as well as accessorizing with elaborate wooden canes.

Although we probably won’t see celebrities in a House of Worth or Madeleine Vionnet original, fashion is cyclical, so there’s numerous designers that have produced collections with late 1800s influence.

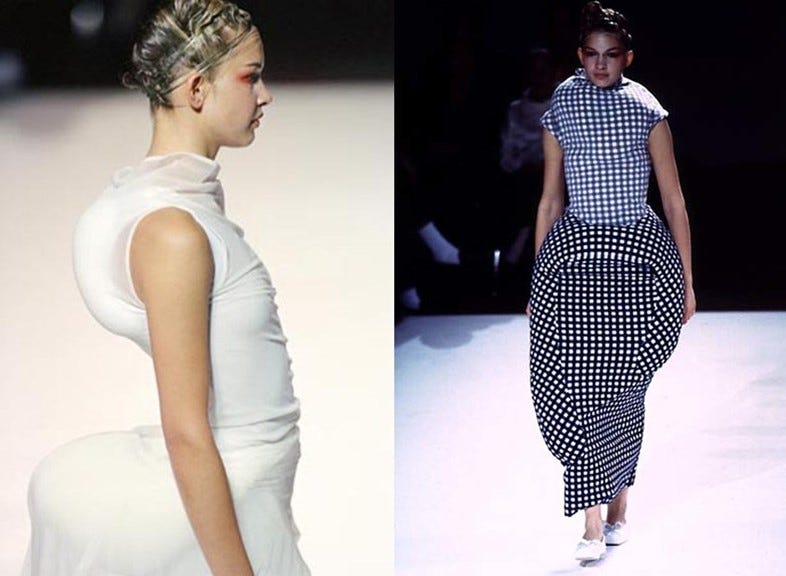

My prediction is that we’ll see a lot of people attending the Met Gala in looks referencing the Victorian era or wearing looks with a Rococo flair. However, I am hoping for bustles galore, and would love to see iterations by Schiaparelli, Vivienne Westwood, or Rei Kawakubo. Even as recently as this past Friday, Thom Browne had a bustle walk down the runway for his Fall 2022 collection.

Rei Kawakubo’s iconic ‘lumps and bumps’ collection saw a lot of emphasis on the backside, and an interpretation of the reverse ‘S’ curve silhouette of the late 1800s. Vivienne Westwood is no stranger to a historical reference and has often pulled from the Victorian era. Her mini shelf bustle skirt would be such a fun take for a younger person in attendance, and her 1994 butt pads would make me giggle. Moschino has done panniers, and I don’t see why he wouldn’t be able to deliver on an over-the-top bustle. In the SS 1951 collection, Christian Dior drew inspiration from the ‘natural form’, while the FW 1951 collection brought back the bustle. Alexander McQueen has also, of course, drawn from 1800s references, right from his first collection.

If someone were craving a more toned down approach, I can’t help but connect the shirtwaist ensemble of the 1890s to Carolina Herrera’s iconic white shirt, tucked into a belted ball-skirt. Seeing a custom Zac Posen gown is always on my wish list, and given the fact that Zac is a master at shaping the female body, I know he’d perfect an 1800s silhouette. Christopher John Rogers would also give what needs to be given; just image the shape! The color!

All in all, I think this theme has the chance to deliver on fabulous over the top looks; let the rich people be rich!!! Unfortunately I have been disappointed year after year, and often beg to understand the thought processes behind the looks designers, and Anna Wintour, have decided to approve.

Either way, see you in a couple of days for the red carpet review, toodles!

TTYL!!!

xx