The History of Sequins

More Than Just A Holiday Adornment

With the holiday season upon us, I predict a sequin or two in your future. Personally, I’m partial to a sequin as part of the everyday as, because I like a little tension. Sequins during the holidays feel a little too obvious for me, but I’ve also worn three different tartans at once on Christmas, so.

Anyway, I thought I’d give y’all a history lesson on sequins in fashion, with a little bit of theory sprinkled in between, because what better time of year to hyperfixate on these shiny little suckers than now? I typed a little over three pages of notes, so, let’s not waste any more time.

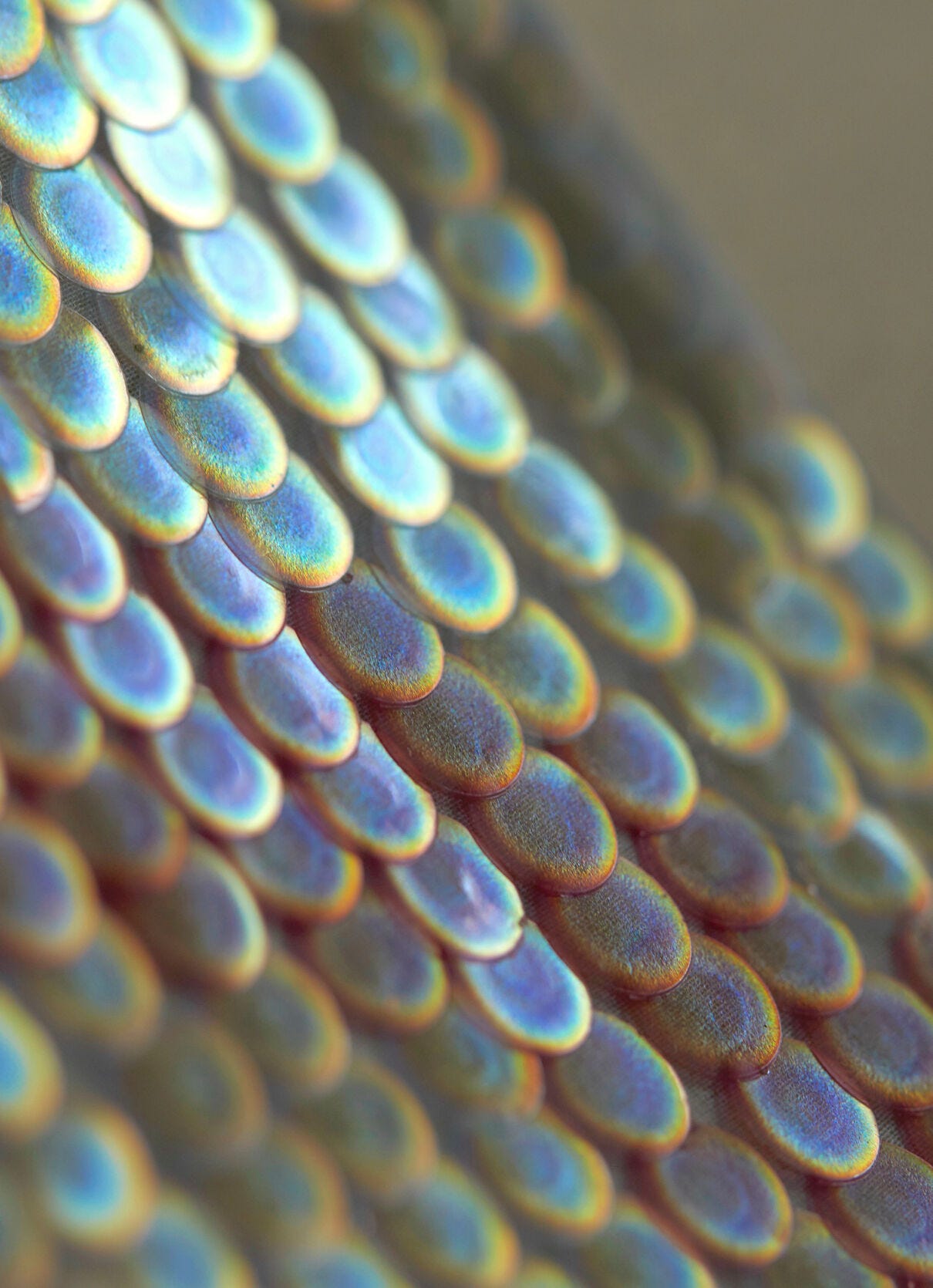

The word “sequin” comes from the Arabic word “sikka,” meaning coin, which later became the Venetian “zecchino”— a Venetian ducat coin. After the Napoleon invasion of Italy, the ducat stopped being mined, which is when the French picked up the name for sequins in the way that we use it today, because, just like the coins, sequins were originally made of metal.

Sequins made from nautilus shells can be found dating back 12,000 years in Indonesia, and there is also evidence of gold sequins being used as decoration on clothing as early as 2500 BC in the Indus Valley. Solid gold sequins were found sewn into the royal garments of Tutankhamun that were said to assure he would be financially and sartorially set in the afterlife. More on the influence this discovery had in a bit!

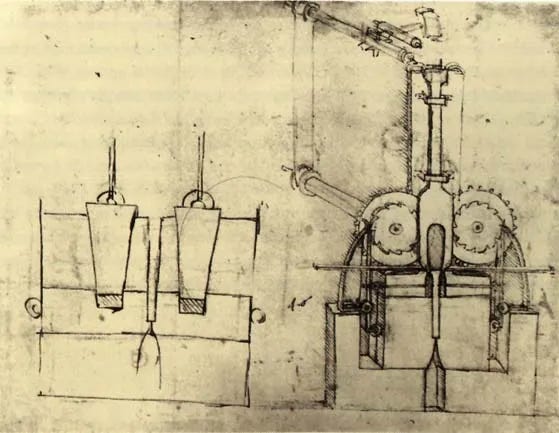

In the early 1480s Leonardo da Vinci actually sketched an idea for a machine that would punch out small metal disks, but it was never made. A man ahead of his time!

It wasn’t until the 17th century, where we see sequins made of small metal disks, known as spangles, in Europe. They were made by punching out the desired shape from thin metal sheets, and were very popular among the European nobility and upper class from the 17th to 19th century. Historically, ornamentation, like the sequin, on clothing was used to display wealth and status, ward off evil spirits with its shine, or to just keep whatever it was secure. The Plimoth Plantation women’s waistcoat is a great example of the ways in which we wear sequins today, with the recreation of the garment featuring over 10,000 hand applied spangles. The Plimoth Musuem’s website reads, “these fashionable items of dress were popular in the first quarter of the 17th century for women of court, the nobility and those who had achieved a certain level of wealth.”

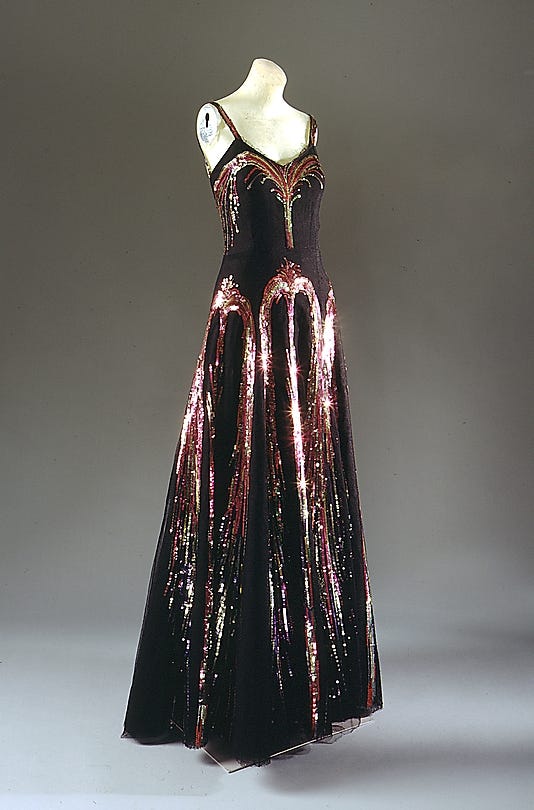

In the Victorian era things got very ostentatious with over the top ornamentation and colors really booming. This continued into the Edwardian era, where the use of spangles became very popular in haute couture. Callot Soeurs, one of the leading fashion houses in the 1910s and 20s, made evening dresses dully adorned in them. S/O to Coco Chanel and the flappers too. Speaking of the 1920s, this was when Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered, and so sequins saw a very big rise in popularity as a result of Egyptomania.

During the Harlem Renaissance, sequins adorned costumes at drag balls, serving as a form of self-expression and resistance, which is something that we still see persisting today.

In the 1930s, we get sequins made of electroplated gelatine, which were a lot lighter than their metal counterparts, however, they would melt if they got too hot or wet, because gelatine. So, no getting hot and steamy on the dance floor with your partner, unfortunately. Also! The color was lead based, so, not ideal. Herbert Lieberman was not down with the gelatine sequins, so with his company, Algy Trimmings Co., he worked with Kodak to produce clear, plastic sequins. In the 1950s, DuPont helped them out a lil bit and invented mylar to surround the sequins with polyester film, fixing their brittleness. Eventually, vinyl plastic replaced this due to durability and cost effectiveness.

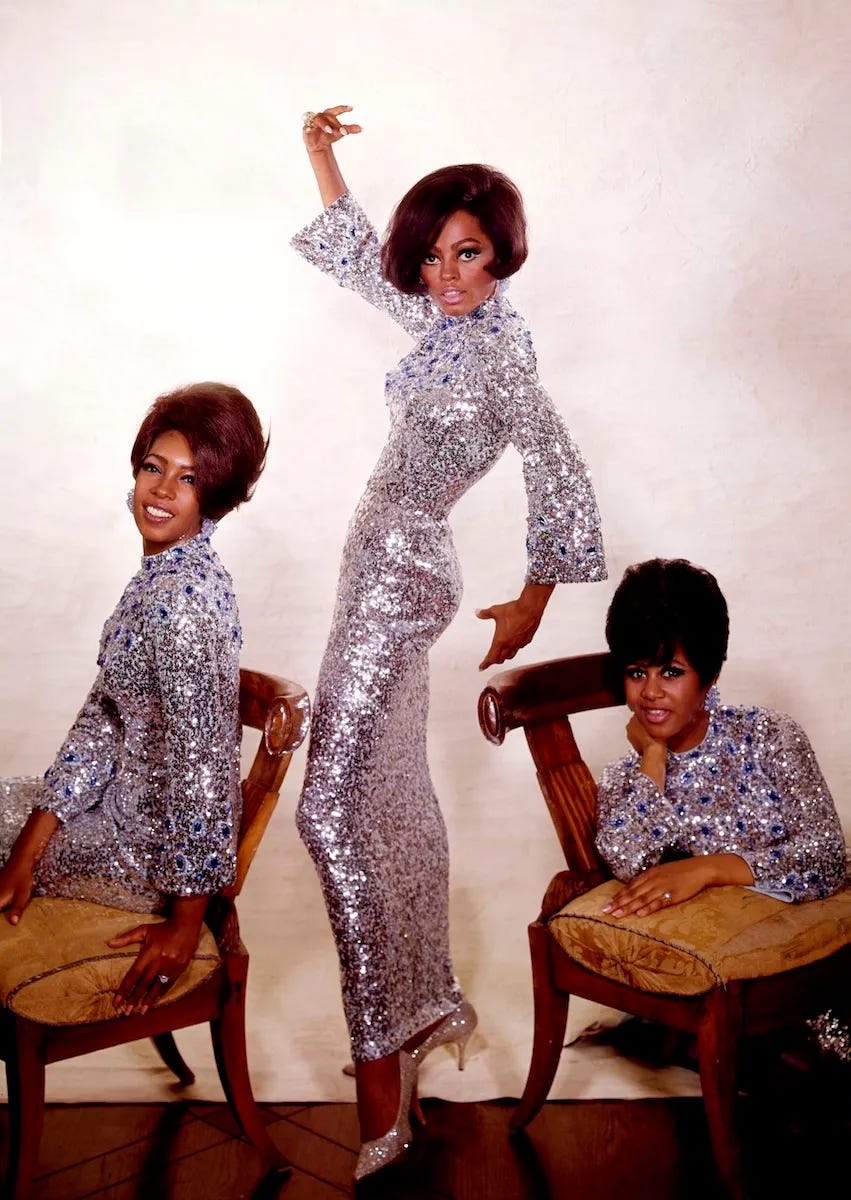

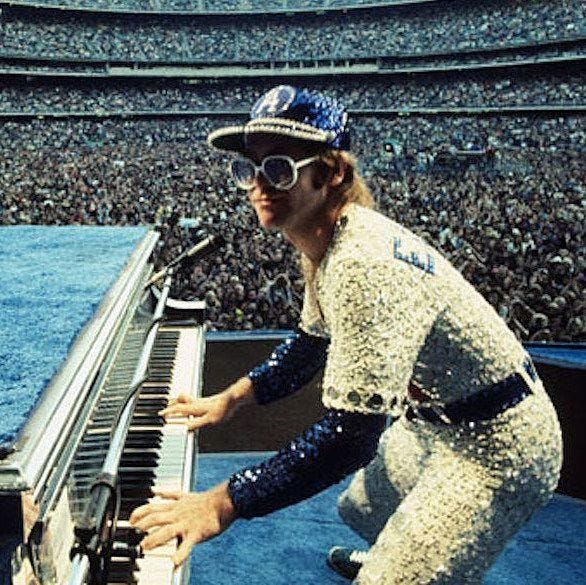

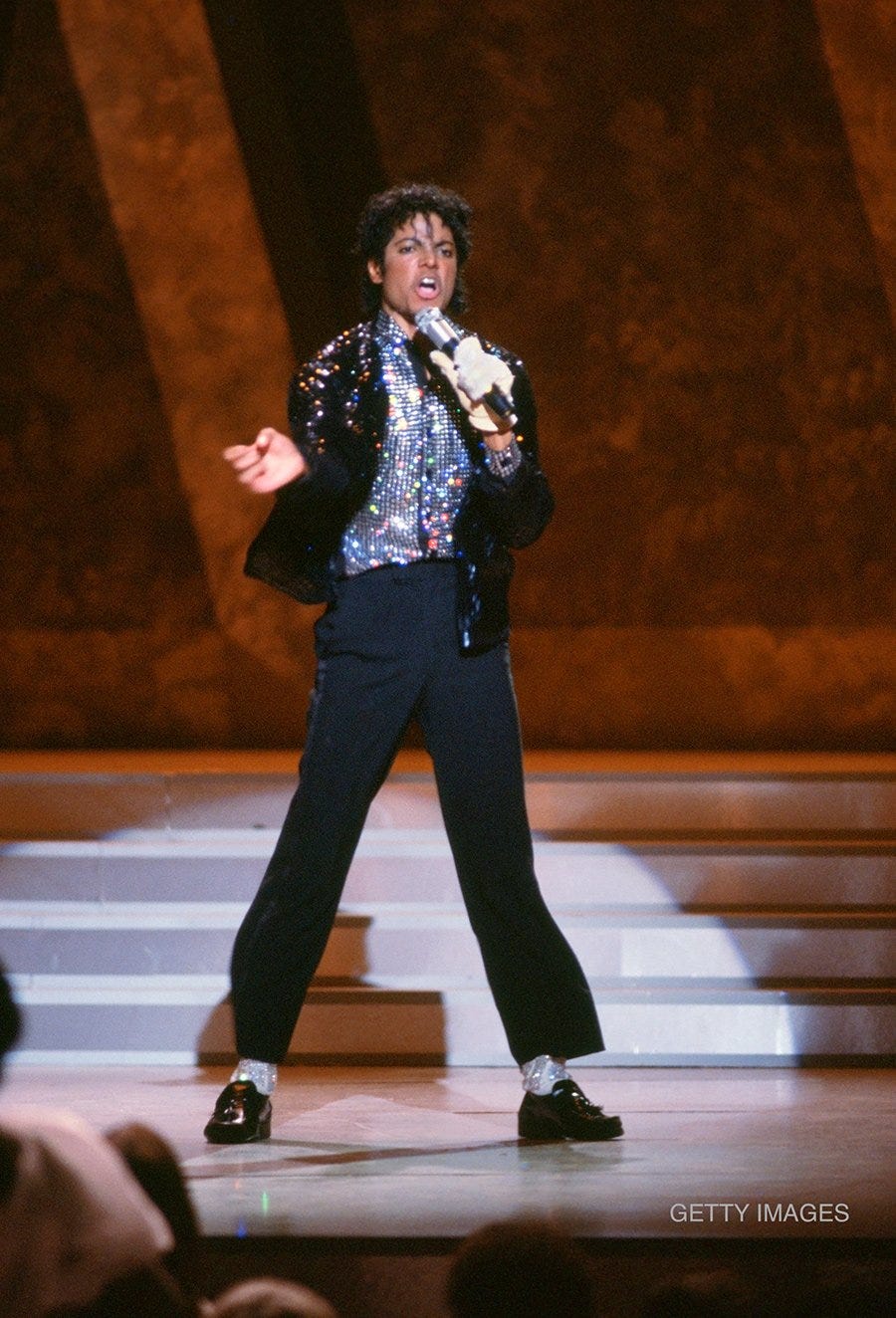

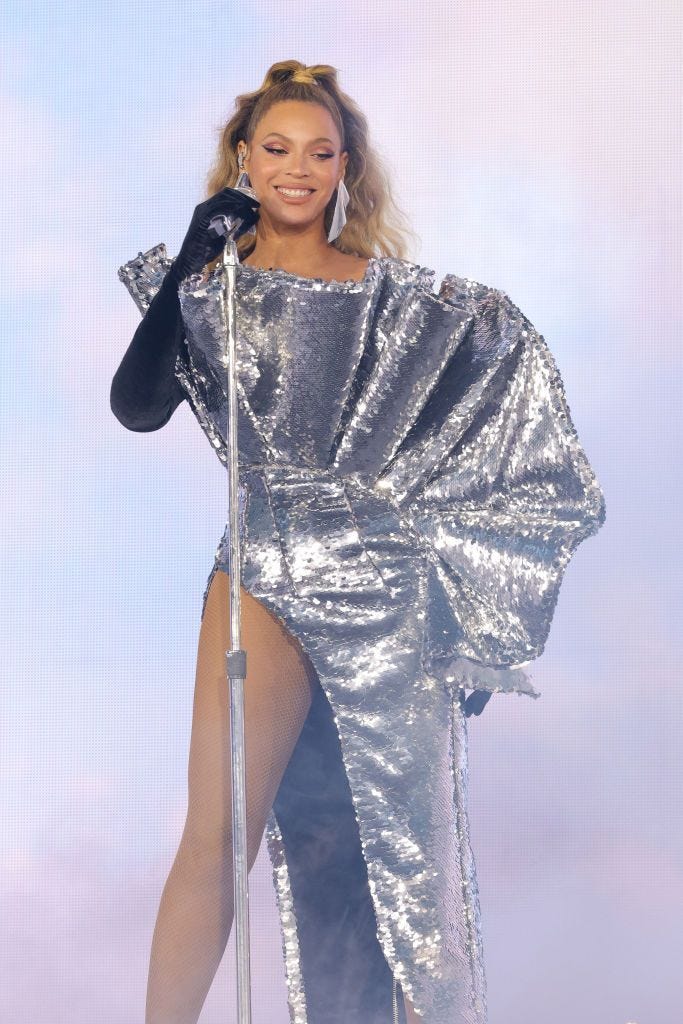

In the 1960s, sequins see another rise in popularity and are worn by a lot of musicians, most notably The Supremes. Mary Wilson recalls their sequin dresses being an armor that changed racial perception during the rising tensions of the American civil rights movement. Then the 1970s brought Studio 54, disco, and glam rock— a breeding ground for for self-expression, fun, and liberation. It also didn’t hurt that the sequins reflected the light of the disco balls perfectly. In 1983 Michael Jackson famously wore a black sequin jacket to perform Billie Jean, and the adornment continued to be a staple in his wardrobe.

As we’ve mentioned, sequins are made of plastic, which is not cute and fun for the environment. More recently, in April of 2023 to be specific, Stella McCartney introduced BioSequins by Radiant Matter. The non-toxic, biodegradable, and low carbon sequins are made without the use of plastics, metals, minerals, or pigments, and are instead made with plant derived cellulose.

While seeing innovation like McCartney’s is fantastic, today, sequins are still very much mass produced. Glamour has become more democratized and Fashion historian Valerie Steele suggests that this democratization creates tension between “high” and “low” fashion, as sequins oscillate between “high art and vulgarity.” Earlier this year, a WSJ headline read: Executive Women Are Wearing Sequins to Work. ‘I Made the Decision to Be Seen.’ Whether worn by a performer on stage or by an everyday individual with a blazer and jeans to balance them out, sequins reject the exclusivity of certain class codes, asserting that anyone can participate in beauty and joy, and at any time.

Then there’s the obvious association with the holidays and festivities. While sequins do embody celebration, in the context of oppression, that celebration becomes an act of resistance. They make joy radical in places that it has been denied. They’ve always been a light in the doom and gloom, with Leigh Bowery once saying, “the reason I use sequins… is because if I cannot cast the light, at least I can reflect it.”

Sequins demand attention by reflecting light, making the wearer impossible to ignore. As bell hooks famously said, “to be seen is to exist.” Throughout history, marginalized communities, particularly queer and Black performers, have used sequins to assert their presence in spaces where they were otherwise rendered invisible.

Following the election, I wrote about how the rise in trad wife fashion made Donald Trump’s win unsurprising. Sequins, although capable of subverting more conservative styles, are the anthesis of this trad wife “aesthetic.” In Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity, Elizabeth Wilson writes that fashion often reflects the ideological struggles of the time, arguing that "dress has always been a principal medium for negotiating identity and morality." Sequins, with their associations of glamour and excess, directly challenge the moralizing undertones of conservative fashion. They disrupt the visual codes of quiet subservience that these looks evoke. Trad wife fashion mirrors broader conservative fears of excess, positioning simplicity and modesty as virtues, while calling back to the 1950s and channeling a “better time.” Perhaps unapologetic self-expression, sequins and all, is something we can expect as a response to this— the same way the 1960s and 70s was a period marked by sexual and social freedoms.

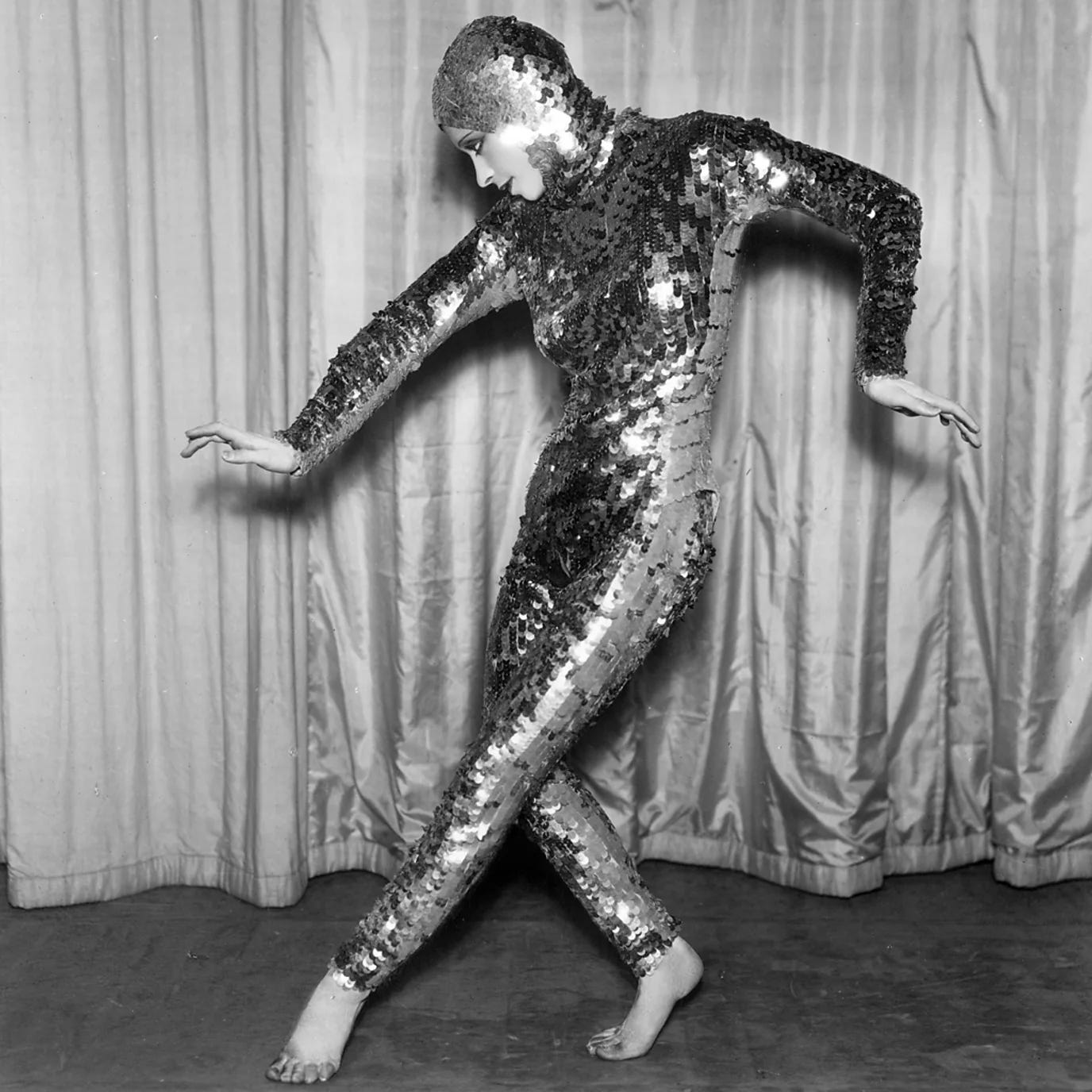

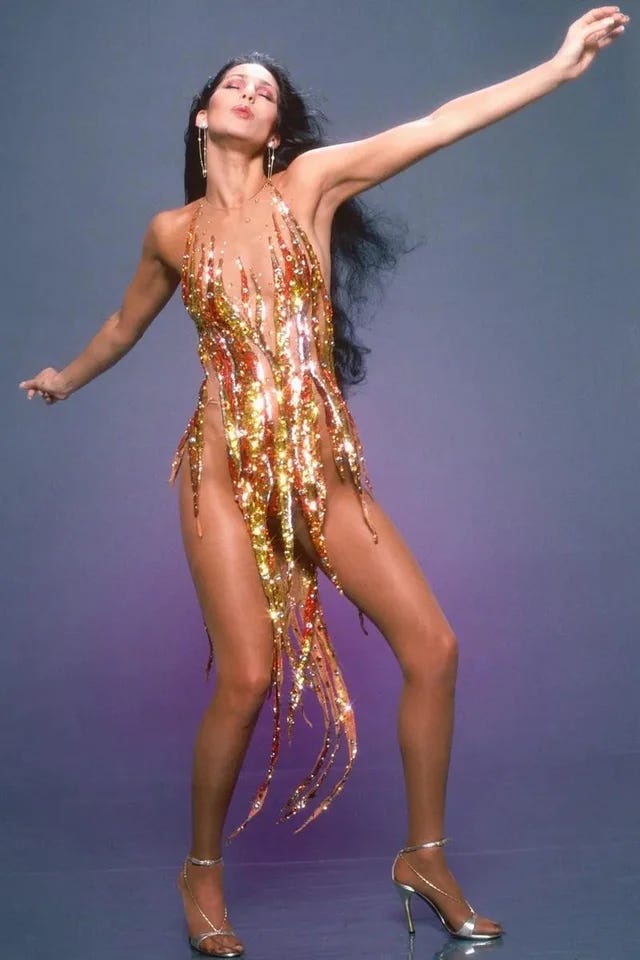

Trad wife fashion perpetuates a performance of traditional femininity, reinforcing ideals of passivity and nurturing roles. Sequins, by contrast, enable a more radical performance of femininity— one that is bold, camp, and often queered. I’d say there’s even something sensual about them, especially when they look deliciously wet. You know I love a wet sequin. Their shimmering surface plays with light and movement, drawing attention to the body in ways that are both celebratory and provocative. Sequins make the wearer simultaneously visible and untouchable— a tension central to fetishism. Consider Burlesque; performers like Dita Von Teese use sequins to enhance the theatricality of seduction, reclaiming the power of erotic display. The sequins themselves become tools of empowerment— they tease you, but they are firm in their autonomy and never imply consent.

Sequins assert that to shine is to survive— and to thrive. So, maybe wearing sequins while arguing with your relatives over holiday dinner is something we should all hold space for.

TTYL!!!

xx