Superfine: Tailoring Black Style

The 2025 Met Gala Theme Explained

Met Gala Monday is finally upon us and I am very excited about this one, but also not looking forward to some of the ways people will talk about it. Anyway, this breakdown is going to be a little bit different from ones I have done in the past, just because I don’t want to regurgitate Monica L. Miller’s work when you can (and should) read her book yourself, but also because I can’t write about it from a personal point of view. Regardless, I still want to come from a place of observance and provide a source for everyone to be on the same page, know the difference between the theme and the dress code, and have a bit of background when they decide to put their fashion critic hats on for the day.

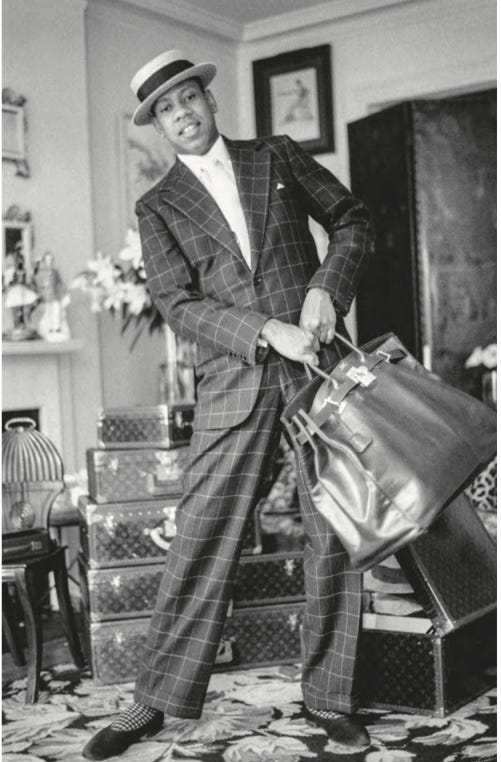

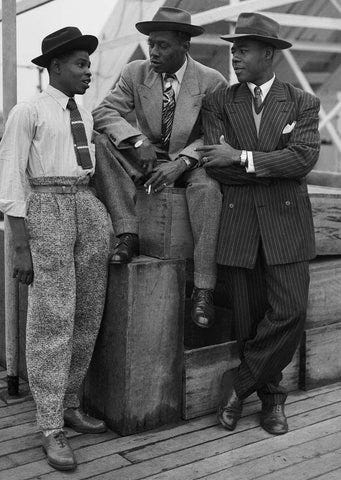

Entitled Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, the Costume Institute’s 2025 Exhibit will focus on the Black dandy, “examining the importance of clothing and style to the formation of Black identities in the Atlantic diaspora.” The exhibit will be based on Monica L. Miller’s 2009 Book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. Miller will be acting as guest curator alongside Andrew Bolton, and in Vogue’s announcement of this year’s theme, she described Black dandyism as “a strategy and a tool to rethink identity, to reimagine the self in a different context. To really push a boundary—especially during the time of enslavement, to really push a boundary on who and what counts as human, even.” and said that the exhibit will “illustrate how Black people transformed from being enslaved and stylized as luxury items, acquired like any other signifier of wealth and status, to autonomous self-fashioning individuals who are global trendsetters.” This is also the first menswear focused exhibit since 2003’s Bravehearts: Men in Skirts, and will see the Black dandy examined from the 18th century to present day.

According to Vogue, the exhibit will be organized into 12 sections, each representing a characteristic that defines dandy style: Ownership, Presence, Distinction, Disguise, Freedom, Champion, Respectability, Jook, Heritage, Beauty, Cool, and Cosmopolitan; inspired by Zora Neale Hurston’s 1934 essay, The Characteristics of Negro Expression. Some additional and fantastic dandy discussions to add to your crash course include: The Making of Vogue’s Met Gala Issue, Complex’s PLEASE EXPLAIN episode on the Black dandy, featuring Dapper Dan, June Ambrose, and Ali Richmond, hosted by Aria Hughes, On Being a Modern Dandy by Jermey O. Harris, Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style by Shantrelle P. Lewis, and Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion by Sowmya Krishnamurthy.

This year’s gala will be co-chaired by Colman Domingo, Pharrell Williams, A$AP Rocky, Lewis Hamilton, and Anna Wintour, with LeBron James as honorary chair. We’ll also be getting a host committee, consisting of André 3000, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jordan Casteel, Dapper Dan, Doechii, Ayo Edebiri, Edward Enninful, Jeremy O. Harris, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, Rashid Johnson, Spike Lee and Tonya Lewis Lee, Audra McDonald, Janelle Monáe, Jeremy Pope, Angel Reese, Sha'Carri Richardson, Tyla, Usher, and Kara Walker. The event will be sponsored by Louis Vuitton and Instagram.

Now, the dress code, which is not the same thing but almost, kind of, is. Playing off of the theme, this years dress code will be Tailored for You— a nod to the exhibits focus on suiting and tailoring, but also a theme that leaves a lot of room for interpretation. A theme that I don’t think they have been marketing and discussing very correctly. The powers that be would have you think that any old suit would be considered dandyism, but I’m hoping the attendees (especially the men) will actually do something this year, instead of just giving us boring, black, suit.

I understand why this year’s Met Gala and this event as a whole may feel performative to some when we consider the ways in which the fashion industry has treated the Black community at large. However, in all its bittersweetness, I don’t think there’s any denying how important an exhibit and a theme like this one are. Tailored for You has the opportunity to be so personal. Showcasing how this is not a costume party; it is a call to reflect. Who gets to tailor themselves? Who gets to be seen as “put together”? In this moment, Superfine is less a theme than a thesis: that Black style is not derivative, but definitive. The exhibit does not simply invite admiration—it demands reckoning. The Black dandy retools the very machinery of fashion, turning performance into power, cloth into code, and suiting into something far more radical than fit.

Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of “cultural capital” traditionally positions elite, white taste as the arbiter of value. Yet it is often subcultures and minority groups that prove trends are a lot more trickle up than they are acknowledged to be. Black people have been the true arbiters of taste, time and time again, only to be “outshined” or repackaged by Hailey Bieber nails and clean girl aesthetics. The Black dandy often plays with codes of high fashion, not to assimilate, but to destabilize them. It’s seen plain as day when Black street and club cultures are mined by luxury houses for inspiration. What was once deemed “urban” or “ghetto” becomes couture— but who gets to decide that?

We all know the rich are historically boring, and I think we can all agree that style often originate not in elite ateliers, but in cultural resistance, everyday ingenuity, and subcultural codes. From hip-hop’s transformation of sportswear into high fashion, to zoot suits and Sunday best as forms of coded rebellion, Black style has always been ahead of the curve, often by years. As Dapper Dan once said, “Style is when they’re running after you, not when you’re running after them.” Miller captures this tension brilliantly when she writes, “...this black dandy is trapped in the performance that produced him, even as he embodies a potentially liberating difference within the very system that defines him.” In other words, the dandy reveals the falsity of the binary between subjugation and style. He is both captive and creator, both decoration and detonator.

This challenging of binaries dates back to Beau Brummell, considered to be the original dandy, who always flirted with gender ambiguity—a man so invested in appearance that he threatened heteronormative masculinity. But when the dandy is Black, this tension intensifies. He becomes a figure who challenges the presumed alignment between race, gender, and power. It is queerness beyond just sexuality. In this way, queerness is about possibilities. It’s about living, dressing, and existing otherwise—not according to how dominant structures say you should. The dandy queers what clothing can signify in the same expressive duality that can be seen in West African masquerades or Harlem drag balls. Take A$AP Rocky for example: From kilts to babushkas, archival vintage to fresh off the runway pieces, his taste is historically literate and globally referential, yet unmistakably rooted in Harlem’s fashion logic—remix, elevate, flex.

Western fashion museums often frame non-European styles as “traditional” or “ethnic,” and European styles as “modern” or “universal.” This chronological binary is racialized: whiteness is future facing; Blackness is past-tense. But Superfine shatters that timeline. It refuses to treat Black style as an exotic relic and instead shows how it has always been modern and futuristic, even when rooted in history. Designers like Wales Bonner, Telfar Clemens, and Martine Rose exemplify this approach, fusing historical motifs with subcultural styles to challenge the idea that Blackness is ever static. We can also look at the Sapeurs who create a parallel modernity, rather than being “behind” Europe. They aren’t trying to catch up to anyone, but instead create a different, spectacular present where their self-styling defines a new kind of time—one marked by performance, celebration, and visual innovation.

Through Superfine we can see the emphasis on tailoring—historically a symbol of Western civility and respectability—recontextualized as a tool of disruption and pride. The exhibit’s title flips colonial language of cloth classification into a declaration of sartorial excellence and refined identity. The enslaved Black person’s image was curated for European visual economies, their identity erased beneath the finery. And yet, as Miller argues, even under these violent conditions, Black style became a counter strategy, not just a costume. Her definition of Black dandyism as “a strategy and a tool to rethink identity” directly contest fashion’s colonial histories, wherein “Black boys and Black men were sometimes luxury items, collected like another signifier of wealth and status.” The tension between being styled and self-styling underscores the exhibition’s historical arc.

E. Patrick Johnson’s theory of “quare studies” insists that performance in Black life is not just theatrical—it is a technology of survival, protest, and intimacy. While white fashion subjects are permitted to “just be”—to have their aesthetics interpreted on their own terms—Black figures are constantly mediated through social fears, stereotypes, or fantasies.

The dandy, as Miller writes, “must choose the vocation,” unlike the fop who is made into one. This act of choosing becomes a form of ontological resistance, asserting autonomy in spaces that were not made to hold Black beings. Spaces like the Met Gala or the front row at a fashion show. The paradox of Black style—hypervisible yet institutionally invisible—is thematized in the gala’s structure. The Costume Institute, long criticized for its Eurocentric canon, is now confronted with the reality that Black people are not just participants in fashion; they are, in many, many ways, originators. Though Black style has long fueled the aesthetic engine of American fashion, it has rarely been credited, cataloged, or curated with seriousness. When included, it has often been through the lens of novelty or exoticism—instead of as integral, intellectual, and innovative. The Black dandy, however, demands to be seen, but not on the terms that were set for him. His suit becomes not only a second skin, but a semiotic rebellion—a way to insert meaning into a visual landscape that might otherwise render him disposable. He is not just flesh, but a site of meaning. Think of André 3000’s iconic looks—his wigs, bows, capes, kilts. They are not just stylistic quirks; they are interruptions in a system that expects Black men to either conform or disappear. Or Lewis Hamilton’s track style, disarming traditional machismo and uniform, while insisting on a spectrum of what can constitute performed masculinity.

So, what would I love to see? Well, I do love a reference and I think the hip-hop community (and really the entire music industry) is full of ones perfect for this event. Speaking of hip-hop, did you really think I could get through this entire post without mentioning that I would love to see Lil’ Kim and Misa Hylton there? The two people I will bring up any chance that I get? I would actually love to see a lot of women there, because I don’t think a discussion around dandyism, especially in modern day, exists without women. Not just the actors and singers, but the stylists and artists as well— those that make it happen behind the scenes. I’d love for them to stop playing in June Ambrose’s face. I’d love to see incredible designers, old and new, like Ozwald Boateng, Thebe Magugu, Theophilio, and Christopher John Rogers. I’d love to see a nod to André Leon Talley, of course, and I’d love if Kanye wasn’t like that so he could be there. I’d also love for Jack Schlossberg and people who don’t understand how the Met Gala works and what the purpose of it is to shut the fuck up.

Anyway, what do we think? Will the carpet be incredible or a disaster? Will white people for once be able to read a room? We’ll see on Monday!

TTYL!!!

xx

![Dennis Rodman's Extremely Weird Fashion Moments in the '90s [PHOTOS] Dennis Rodman's Extremely Weird Fashion Moments in the '90s [PHOTOS]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!iGFM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F201ab3ba-e717-420e-a839-039fe09bb5cc_683x1024.jpeg)