FINALLY! As you all know, I am Luca Guadagnino pilled, so it’s very unlike me to have taken this long to watch one of his movies. With that being said, I already know this is going to be one of those movies that hits me even harder on the second watch. I also can’t help but think about all the people whose introduction to Luca was Challengers, and naturally they decided to see this after, lmao. My sweet children, how are we doing?

There’s many reasons why I love his movies so much, but one of them being that they’re all so different yet still very distinctly have his touch. Queer was a lot more stylized and abstract than a lot of his work, but I don’t like being spoon fed information anyway, so.

Anyway, as usual, don’t get mad at me for spoilers. If you choose to read on without having seen the movie yet, that’s on you xoxo.

Based on the novella of the same name by William S. Burroughs, Queer follows American expatriate (William) Lee. Lee is escaping drug charges in a post WWll Mexico City where he is dealing with addiction, withdrawal, and having relations with younger men. Enter (Eugene) Allerton, a discharged navy officer, who Lee becomes infatuated with. While Allerton might seem like he has it all together, he is unraveling at the seams just the same as Lee, even if more subtly. Their ayahuasca filled trip to Ecuador makes that more clear, while their tumultuous relationship only adds to Lee’s psychological and existential distress. Guadagnino’s Queer presents a story that is steeped in existential displacement, addiction, and the painful liminality of desire. Through dreamlike scenes that have you questioning what is real and what is imagined, he explores the emotional journey of unsynchronized love.

Costumes were done by Jonathan Anderson (king), who also did the costumes for Challengers, however this one was more of a fashion history nerds dream. Everything was entirely vintage from the 1940s/50s— save two identical white suits and the centipede necklace worn by Omar Apollo’s character. During this time period following the war, the United States experienced a surge in textile production. Clothing was being mass produced and everything they no longer needed was exported to Latin America, so Anderson very much did his research and sourced most of these clothes from Mexico.

Not only did he prioritize historical accuracy to ground this hyperrealistic fantasy of a movie, but in conversation with Variety he also mentioned how the clothes had to communicate with the audience, adding that, “You have to be able to read character before they even speak because it’s about the action and the visual.” There’s a subtly to the wardrobe and the storytelling that makes the queerness less overtly flamboyant and more spectral— existing in the subtle, lingering details of a worn-out collar, a slightly oversized jacket, or a gaze that lingers too long. Inspiration was also taken from Michaël Borremans, Glyn Philpot, and George Platt. Anderson is no stranger to allowing fashion and art to collide on the runway, but here more specifically, Borremans’ paintings often depict figures in surreal, disjointed settings, much like Lee himself— physically present but emotionally adrift. While, Philpot’s dreamy portraits of men capture a tension between refinement and latent desire, and Platt’s photography delves into queer sensuality and the act of being seen. Burroughs himself was also on the moodboard, most clearly seen in Lee’s constantly unbuttoned top button and his final look.

As both Lee and Allerton are expats, it would make sense that their entire wardrobes could fit into a suitcase and would consist of pieces that would be a result of the mass production happening in the United States. In that same Variety article, Anderson mentioned that he wanted the audience to be able to smell Lee’s suit. To see its worn in knees, sweat stains, and cigarette smudges and to understand the sensory experience of being in its presence. These stains are not at all incidental; they are a physical archive of his decline and the bodily wear of addiction.

Lee is not only an expat but also a human embodiment of discarded American culture, existing in a space where he does not fully belong. His clothes, much like his presence in Mexico, are remnants of another place and time. In The Fashion System Roland Barthes notes that “fashion is simultaneously a ‘real’ system, grounded in social structures, and a dream system, projecting desires and illusions.” Lee’s wardrobe embodies this tension: on the one hand, it grounds him in the economic realities of postwar Mexico, where second-hand American clothing floods the market; on the other, it serves as a projection of his fractured identity, a longing for a sense of belonging that remains eternally out of reach. His wardrobe becomes the material evidence of his disembodiment, and the more he declines in physical and mental health, the more disheveled his wardrobe becomes. We see him starting off in a pristine white shirt, like pure cocaine. Then it starts to turn brown as if stained with heroine, and finally we see him wear black, like tar. In the epilogue he tries to appear put together, just in case he sees Allerton again, but no one’s falling for it. This moment reflects a final tension between presence and absence, between self-possession and disintegration. His clothing may be arranged more neatly, but the viewer, having witnessed its previous degradation, understands that this is merely a temporary illusion.

The loneliness and despair we see in Lee and the clothing that hangs off of him like off of a decaying corpse, is quite the opposite of Allerton’s preppy and polished image. He’s the perfect, all American boy, and his sureness is something Lee is hungry for. His desire is so strong that not even being under Allerton’s skin would be enough. But, no amount of polos, fitted knits, freshly ironed pants, and lively colors can conceal that he too is fraying at the seams.

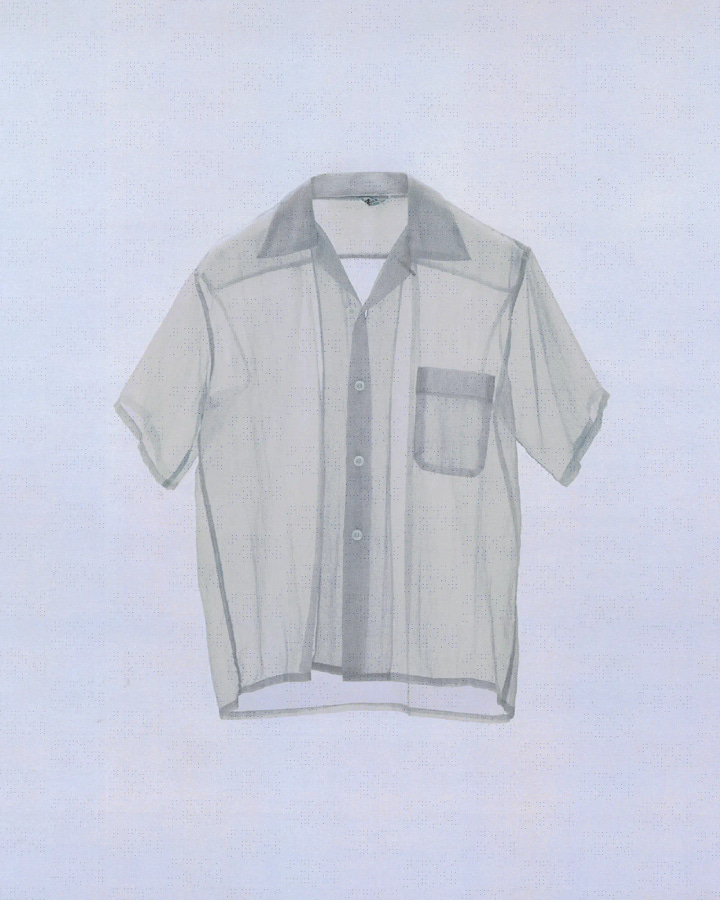

Allerton is someone who cares about his appearance and the way in which he is perceived. Clothing wouldn’t have been cheap during this time, so one can infer that it’s something he prioritizes, sine he definitely doesn’t have much to spend. He builds an armor with his clothing, but as time goes on and he opens up to Lee more, his exterior becomes softer. At first, he is untouchably composed, but as his relationship with Lee develops, the integrity of his wardrobe shifts. His shirts become more translucent, his crispness gives way to softness, and the careful image he projects begins to unravel more and more.

It becomes hard to tell what’s real and what is just a figment of Lee’s imagination. Allerton’s mirage like existence parallels Philpot’s paintings, whose subjects often felt like transient beings. His translucency becomes a visual metaphor for his increasing vulnerability. Lee projects so much onto him, seeing him as a fixed object of desire, but Allerton is not static— he is slipping away even as he stands before him. His wardrobe mirrors this instability, reinforcing the notion that he is, in many ways, an illusion. Consider his swim trunks, and really the whole scene at the beach. It’s an almost cinematic choice and a departure from his otherwise structured attire. Here, he seems less like a man weighed down by social expectations and more like a fleeting vision, existing outside of reality. If Lee’s wardrobe is about bodily disintegration, Allerton’s is about controlled dissolution— a sartorial mirage that shifts as the light changes. In A Lover’s Discourse Barthes describes the lover’s object of affection as a “mirage of perfection”— not a person, but an idealized construction. Allerton’s wardrobe, with its pristine preppy signifiers, functions as an extension of this fantasy of control and desirability.

Then there’s the bar guy, played by Omar Apollo. His presence in Queer is fleeting, yet his costuming leaves an indelible impression. He exists as a moment of possibility, a figure of seduction and ambiguity. Through the tension between his structured exterior and the intimate, coded garments beneath, Anderson crafts a a cipher of transformation, a figure caught between past and present, repression and revelation. The crocheted tank top he wears under his suit and button up shirt was developed in the 1950s as an undergarment, meant to be hidden and never seen. Yet, it has become a staple of the queer rave scene to this day. The bar guy is neither fully hidden nor fully revealed, neither entirely constrained by heteronormative structures nor completely liberated from them.

That lingering repression that reigns throughout the film is most notably represented by his centipede necklace. As Lee fished it out of its net, the net itself suggests entrapment, the act of retrieval mirroring Lee’s own desperate attempts to grasp something elusive. The centipede, a creature associated with adaptability and resilience, embodies the film’s core tensions: the struggle between repression and revelation, the fear of desire, the anxiety of being consumed by one’s own longing. In many cultures, the centipede represents transformation and healing, its ability to regenerate lost limbs reinforcing themes of survival and endurance. Lee’s grasping it underscores his own entrapment within cycles of yearning and denial.

In Queer, clothing is more than mere attire; it is a living archive of desire, a fabric of unraveling identities, and a testament to the inescapable tension between visibility and erasure in a world that offers no refuge to those who exist at its margins.

Also, I saw someone say this was gay Space Odyssey.

TTYL!!!

xx